Japan and the European Union have similar approaches to peacekeeping that can become the basis for cooperation in their regions and beyond

Japan and the European Union have similar approaches to peacekeeping that can become the basis for cooperation in their regions and beyond

Filed under Home

As speculation simmers about the coming together of alliances or coalitions to counterbalance, deter, or confront the People’s Republic of China (PRC), such as an Asian NATO, a Quad plus, or a possible invitation to Japan to join the long-standing Anglo-Saxon “5-eyes” intelligence club (consisting of the US, UK, Australia, New Zealand and Canada), a new multilateral institution bringing together resident and outside powers for mutual security action has been largely overlooked.

Tucked away in North East Asia for the last two years, the Enforcement Coordination Cell (ECC) is a multilateral staff headquarts that includes Japanese, South Korean and French navies with their Australia-Canada-New Zealand-UK-USA “five eyes” counterparts and may be considered a hidden gem of Asia-Pacific security cooperation. So why has hardly anyone heard of it?

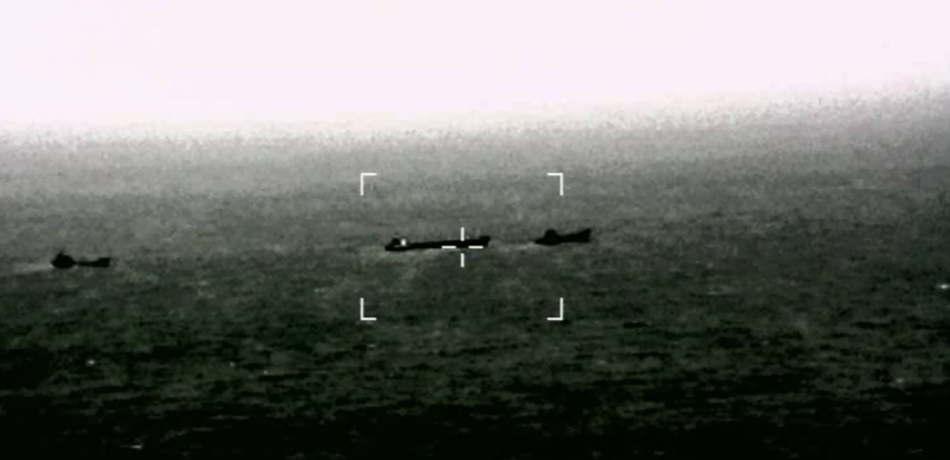

The ECC coordinates the collection and fusion of information on violations of UN sanctions on North Korea (DPRK). The cell is based on the US Navy 7th Fleet ship USS Blue Ridge, but draws on data collected by the ships, planes and other surveillance platforms and mechanisms in a coalition that could be called an Asian ‘Five Eyes + 3”. According to US government officials “The effort is primarily focused on illicit North Korea exports of coal and refined petroleum” and looks at trans-shipments of fuels aimed at getting around sanctions. Here is how the ECC was described in the 2019 US Indo Pacific Strategy Report –

“PARTNERSHIPS WITH PURPOSE

An important example of partnerships with purpose is the Enforcement Coordination Cell (ECC) in Yokosuka, Japan. Commanded by USINDOPACOM and executed by U.S. Seventh Fleet, the United States is working sideby-side with South Korea, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, France, and the United Kingdom at a single headquarters to enforce the UNSCR sanctions regime against North Korea and the illicit transfer of oil and ship-to-ship transfers in the East China Sea and Korea Bay. The ECC allows us to work closely with our allies and partners to manage, coordinate, and de-conflict our efforts and is an importantfacilitator of transparent collaboration betweenour allies and partners at sea and in the air.”

The ECC is a curious animal, though. It does not fit neatly with any of the normal categories or criteria of coalitions, and in some ways it bucks the received wisdom on the limits of what is politically and operationally possible in this region.

1. It is a multinational mechanism that is not framed by a treaty or explicit diplomatic framework. Its purpose is to monitor UN sanctions, and so you might think it would come under the UN rear command that has been based in Japan since the 1950s, when the Korean War ended. But it doesn’t. It is not even clear from reading reports to the relevant UN sanctions committee that the information it collects goes to the Security Council. For whatever reasons, this is a case where adhocracy may be more operationally successful than it might be in a formal diplomatic framework like an ‘Asian NATO’, a ‘Quad’, or even the full United Nations Organisation that provides its rationale.

2. Japan and the Republic of Korea (ROK) have their differences. Territorial disputes over islands, rancor over the history of the ‘comfort women’, and most recently a legal dispute over forced labour from the WWII era that has spilled over into toxic threats on trade and investment, as well as adding an irritant to important diplomatic, intelligence and security ties. And yet, in the ECC, Japanese and Korean armed forces cooperate on monitoring sanctions on the DPRK.

3. The ECC demonstrates how many countries from outside North East Asia are willing to commit to security in the region. This is not a NATO mission, but it includes officers from the UK, Canada and France. Australia and New Zealand are also taking part in the cell as well as providing advanced platforms for surveillance. There has even been speculation that a German navy vessel that is planned to sail to the region in 2021 might take on the enforcement monitoring role for a spell.

4. Perhaps as or more significant than the countries who are in this multinational force are those who are out. UN Security Council Permanent Members China and Russia – who after all voted for the sanctions on DPRK – are not only outside the ECC structure, some of their behaviour at sea suggests that they do not welcome the presence of a multinational force in the region.

Canada refers to its contribution as “Operation NEON“, and seems set to maintain a long term commitment. “During 2019 and 2020 and into 2021, Canada will periodically deploy military ships, aircraft and personnel to conduct surveillance operations to identify suspected maritime sanctions evasion activities, in particular ship-to-ship transfers of fuel and other commodities banned by the United Nations Security Council resolutions (UNSCR). This contribution will bolster the integrity of the global sanctions regime against North Korea.” On Opeation NEON Canada deploys a naval frigate, a supply vessel, and long range patrol aircraft. The surveillance platform CP-140 Aurora, crew and supporting personnel operate from Kadena airbase in Japan and The Canadian Armed Forces “may also provide up to three permanent liaison officers to the Enforcement Coordination Cell, a multinational staff headquarters” in Yokosuka.

In an innovative twist, the Canadian operation is linked to an information fusion project run by the oldest UK thinktank, RUSI. RUSI’s “Project Sandstone“, is an effort to systematically analyse and expose North Korean illicit shipping networks using open source data-mining and data-fusion techniques to spot activities of interest without reference to classified data. According to the Government of Canada “an unclassified set of Canadian data is transferred to Global Affairs Canada, who have contracted the Royal United Services Institute to conduct a deep analysis of the data using open-source information. The Royal United Services Institute prepares and releases reports to Global Affairs Canada that highlight and identify networks and individuals that may be involved in activity that supports sanctions violations (e.g. financing, insuring, etc.). Some reports have been shared with partner nations, and the intent is to further share a consolidated report with the UN.”

The ECC has recieved only limited exposure outside the specialist defence media, with this September 2018 WSJ article proving the rare exception. Does it deserve more attention?

With no end in sight to the stand-off between the DPRK and the UN over the DPRK’s nuclear weapons program, the ECC is becoming a more or less permanent fixture in the region. If it were to collect more members and aquire more tasks, that would not be the first time an ad hoc mechanism has evolved to a permanent feature shaping the security landscape and altering the calculus of regional actors. Meanwhile, it provides a platform for cooperation among a set of “like minded” nations to build up interoperability, regional situation awareness, and a reason to maintain a presence in the region should other contingencies arise.

Filed under Home

How should the British interest be advanced in new circumstances, when Asia is up, Europe is down, and America is – for the foreseeable future – out? Read on in The British Interest

Filed under Home

Today is a birthday, so here`s a party game: Guess the date –

Europe`s political independence and economic prosperity is at risk. As Russia extends its influence across Europe, the UK — a keystone of European security — teeters ambiguously on commitments to integration with its continental neighbors. The costs of recent wars have left Americans sore and in debt, and re-assessing the necessity of defending Europe while threats and instability gather across the Pacific in North East Asia. Bracing against an impending economic slowdown, the United States puts domestic economic concerns before foreign commitments – particularly where they feel like Joe taxpayer and sergeant Jane might be carrying the security burdens of allies that are also economic competitors.

April 2019 or 1949?

In some ways today`s trans-Atlantic scene resembles the situation 70 years ago when the North Atlantic Treaty was signed in Washington DC. Will allies gathering to celebrate NATO`s 70th birthday embrace the ambivalence and the need for adaptation that have always been part of its story? Given broader geopolitical developments, questions naturally arise about its suitability for current conditions, and if it is set up to be around for another 70 years. Addressing these questions also means thinking about the things that make our world so different from that of 1949. Two stand out:

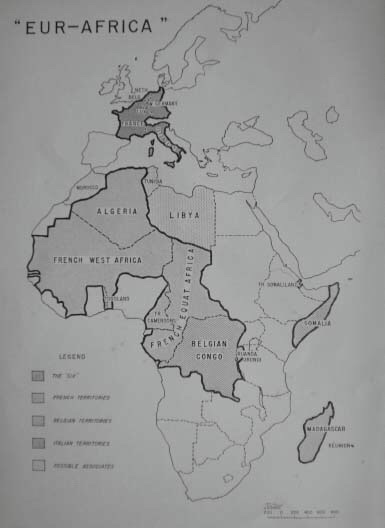

The first difference is how much Europe mattered in American eyes for the challenges of ordering the world of 1949 compared to today. One reason America committed to European security back then (before de-colonization got going) was European power still extended across the world. The loss of the UK, France, Italy and the Netherlands to Communist influence would mean not just the loss of some European territory. It could destabilize colonial territories that were vital to US interests such as Malaya and Singapore, Indonesia, Indo-China, and vast areas of Africa – not to mention old dominions and new commonwealth members, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa, Pakistan, and India. In his history of that time “Grand Improvisation: America Confronts the British Superpower, 1945-1957”, Derek Leebaert recalls the extent to which the US relied on the British Empire, the Sterling area and European colonial governance to hold the ring against the advance of global communism.

European economic recovery, growth and integration over the last 70 years has given it a form of economic and regulatory power that can be very influential, but from an American (global) geo-strategic perspective Europe today is simply less important than it was in 1949. America now has its own worldwide archipelago of military infrastructure that rolled out as the Europeans retreated. The strategic value of European basing for the Cold War US military derived partly from geographical proximity to Russia and the Middle East, but the declining Russian threat (compared to what the USSR presented to America) and emerging US energy independence (thanks, fracking) have further eroded the logic of a “Europe first” policy. The success of the European project has itself raised questions about the centrality of NATO as some Europeans begin to imagine a world where they provide for their security without relying on help from across the Atlantic.

The second big difference is that great power competition in 1949 was shifting to a USA-USSR axis (through Europe) and today it has swung away from the Atlantic to a USA-China axis. A move to rebalance military resources to favour the Indo-Pacific confirm that hemisphere is seen as more important than the Atlantic. As Edward Lucas noted recently “Russia’s economy is the size of Italy’s. Its defense spending is the size of the combined military budgets of the Nordic and Baltic countries, plus Poland. But whereas those countries have only to defend themselves, Russia has to pay for a military space program, nuclear weapons, and a blue-water navy.” The USSR economy peaked at around 60% of US GDP, today`s Russia is closer to one tenth. China on the other hand has been going in the other direction, with a steady rise in military spending and power.

While the prize in today`s great power competition is still the same – the freedom to set a world order advantageous to one`s own economic and strategic interests – the character of the competition is different in ways that make NATO if not “obsolete”, let`s say maladjusted. Instead of the ideological threat Communism posed to the US-led global order, intramural arguments among NATO allies about Iran sanctions, Huawei and 5G infrastructure suggest that today`s threat comes in the form of trade, investment and technological competition. US allies and a new “non-aligned” set of nations are attracted to the low cost and high quality of Chinese offerings. The strategy of containment laid out in 1946-7 into which NATO was born was the response to the threat global communism posed to Western interests. Is it possible to imagine anything like it against an economic, technological giant integrated into the global economy like China? Geographic distance has become less relevant. With Italy subscribing to China`s Belt and Road Initiative, NATO borders do not seem to be insulating Europe from Sino-US tension, nor is NATO solidarity binding the West together on a common strategic response.

Turning to conventional military aspects of rivalry, the tools and weapons that characterize today`s competition are also different in ways that do not seem to play to NATO`s traditional strengths. Threat perceptions towards China and Russia highlight two developments in the changing character of warfare, which NATO must also address to have a secure future. One is “upwards” in the cost of weapons, platforms and systems as the application of technology like Artificial Intelligence, quantum computing, lasers, and hypersonic drives opens domains of competition in space and cyber domains. All areas where national industries compete, rather than work together strategically. The other trend is “downwards” as operational concepts for waging war below the threshold of conventional application of force – so called “grey zone” war have been tested and refined in Crimea and the seas of the Western Pacific. Civil / military distinctions that are wired into democratic cultures make them uncomfortable fighting in the grey areas.

So when NATO turns 70 on April 4th 2019, the allies face profoundly changed geopolitical conditions. Germany has gone from a nation divided and occupied by the victors of WWII to being the largest European economy, its Chancellor even lauded as “leader of the free world”. In Spring of 1949 China was also divided between nationalist and communist forces engaged in a civil war. What changes of comparable magnitude will arise in the coming period?

NATO 2089

To endure far past its 70th anniversary NATO will have to address the trends of reduced security interdependence between Europe and North America, a geo-economic power shift to China, and a bi-polarisation in the character of war (upwards to a high-cost technological arms race, downwards to grey zone warfare). Here are three courses to consider in response:

A more European NATO seems the most intuitive strategic option, but would require a more serious commitment to strategic alignment and to Article 3 of the NATO charter, which commits allies to “maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack”.

Economic interests across the Atlantic do not appear to be converging. President Trump sees the EU as a “foe” on trade. For instance, the US would like to sell Europe more of its agricultural goods, but the EU prefers to exclude the agricultural sector from a trade deal for its manufactured products like cars, and has ruled out concessions that would undercut its protected farming sector. The prospects on technology hardly look better. Chancellor Merkel pushed back after a leaked letter from U.S. Ambassador to Germany Richard Grenell to German Economy Minister Peter Altmaier suggested US intelligence cooperation with Germany would suffer if the German government allowed Huawei into its 5G networks.

A more Atlantic NATO would have to become as comfortable in diplomatic domains of trade and investment as they are on military matters. Economic analysis has been conducted at NATO Headquarters for some time, and an Economics and Security Committee operates as part of the NATO Parliamentary Assembly, but do such issues need to be raised to a higher level in the North Atlantic Council in order to develop common positions on strategic issues like 5G, or the Russia – Germany gas pipeline North Stream 2?

The instruments are there, and given the political will this could be approached with a more purposeful handling of Article 2 of the Charter, which says NATO allies “will seek to eliminate conflict in their international economic policies and will encourage economic collaboration between any or all of them”

This question is also driven by technology. Inter-continental missiles did not even exist in 1949 but today`s cyber and space weapons operate in a domain that is no longer regional but truly global. Does the idea of a regional security organization still make sense in a world a where geopolitical balance and technology are globalizing security?A more Global NATO would mean teaming up to promote allies` common interests in the face of rivals` expanding power and influence. By this logic, the biggest issue confronting the alliance is not even in the Atlantic area, and that is the question of how to accommodate the rise of China and the centrality of Asia in economic, political and military terms.

Are the founding principles of NATO – democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law – appealing enough to cement a meaningful global partnership? After the Cold War ended NATO built up a set of partners around the globe, such as Japan, South Korea, Australia and others – many of whom participated in the broad coalition of over 50 nations that fought in coordination with NATO in Afghanistan. Would these values now be strong enough, (or threatened enough?) to transform into a global Alliance? Probably not. Although the EU Commission branded China “an economic competitor in the pursuit of technological leadership, and a systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance” in its EU-China Strategic Outlook, the reception just given to Xi Jinping during his recent visit suggests not all parts of Europe share a common view, let alone agree with the US position that China is a “strategic competitor”.

Following the course of going global would tap into some of the original sources of trans-Atlantic solidarity dating back to the 1940s. Making European security matter more for global security would be a powerful force for cohesion, but it would also involve a major transformation of an organization configured (legally and psychologically) to promote stability and wellbeing in the North Atlantic Area. The NATO charter has been amended only twice: 1951 on the accession of Greece and Turkey and 1962 to adjust for the change of Algerian departments of France. Amending article 6 (that delineates the region for collective security) and Article 10 (that restricts membership to “any other European State in a position to further the principles of this Treaty and to contribute to the security of the North Atlantic area”) would open up fundamental questions about the direction of world politics in the 21st Century.

Conclusion: A decade of “Labour and Sorrow”?

Is NATO`s 70th a good time for a big birthday shake up? Problems attend each of the directions described above. But for every objection to becoming more European, more Atlantic or more global, there are is an equally good reason to doubt “business as usual” is an option. Some combination of elements from the above will probably be needed for the Alliance to adapt and survive. The United States is led by a President who seems to have little sympathy for multilateral methods, and may be contemplating leaving the alliance. The US Congress demonstrated how seriously they see this question by going to the trouble of voting through notions of support in July 2018. But the examples above do indicate that challenges facing the alliance lie beyond the White House.

`Threescore years and ten` was once reckoned a good lifespan and some already see NATO “dying”. That is probably premature but in preparation for the challenges ahead it is worth reflecting on the King James Bible translation from Psalm 90 in full:

“The days of our years are threescore years and ten;

and if by reason of strength they be fourscore years, yet is their strength labour and sorrow;

for it is soon cut off, and we fly away.”

The question of what role European nations and institutions should play in Asian Security has been given a twist by the Brexit decision and what it reveals about people’s differing assumptions on the UK relationship to its European neighbours. Britain’s pivot to Asia (which stared around 2011 before Brexit was even a twinkle in David Cameron’s eye) is starting to bear fruit just as the leave/remain battle approaches its climax in the lead up to the magic date of March 29th.

UK Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt’s speech at the IISS in Singapore (Britain’s role in a post-Brexit world) has set off the latest round of discussion about how much Brexit has or should have to do with European engagement in Asian security. It was just preceded by an interview given to the Telegraph by the UK Defence Secretary, Gavin Williamson (30 December 2018) in which it seemed that the UK was determined to open new bases in the Caribbean and South East Asia.

The FT responded first with an article by its chief foreign affairs commentator, Gideon Rachman: The Military aims of ‘Global Britain’ should be realistic: opening a base in Asia is not the best use of scarce resources.

With less than three months to go until Brexit, the race is on to define that elusive term, “Global Britain”. Gavin Williamson, UK defence secretary, announced this week that Brexit is “our moment to be that true global player once more — and I think the armed forces play a really important role as part of that”. Fleshing out this ambition, Mr Williamson revealed in a newspaper interview that the UK intends to open two new military bases overseas — one in the Caribbean and one in south-east Asia. He placed particular emphasis on the idea that Britain is reversing its decision, made in the 1960s, to withdraw its forces “east of Suez”. “That is a policy that has been ripped up,” the defence secretary asserted. A great deal has certainly changed in the half century since that strategic retrenchment. But few of those changes suggest that it is a good idea for Britain once again to seek a military role in Asia.

Gideon Rachman concludes that:

The group of democratic nations that is best placed to balance a rising China is the “quad” of the US, Japan, India and Australia. The addition of British or French military resources might add some symbolic force to the effort. But it could also complicate matters, if China decided to follow its favourite playbook and target the weakest link in a coalition with an economic, diplomatic or even military response. The British government’s urge to present a confident face to the world as Brexit looms is entirely understandable. But military ambitions, without the resources to back them, risk making the UK look foolish rather than forceful.

Shortly after, the question of whether the UK has the capacity for playing a ‘realistic’ role in Asian security was answered by the Henry Jackson Society ‘Audit of Geopolitical Capability’ that used a detailed set of statistics to argue that Britain has the potential to be the number two world power. James Rogers, who compiled the HJS report (and is also director of the HJS Global Britain Programme) responded to Gideon Rachman’s opinion piece thus:

The FT op-ed got some pushback from Australian strategist Euan Graham

The base issue was only the start. When it came to the context behind – the conception of Global Britain’s role in the world, other prominent commentators were less supportive of the Foreign Secretary’s ambition:

Objections also arose in terms of priority (local security in Europe is more important):

The situation looks confused and well it might, since it is the result of several things happening at once:

When it comes to European security and the future role of the UK, the issue boils down to three questions -each with their own links to the Brexit issue:

Britain, along with its democratic allies around the world, should certainly seek to play an active role in maintaining peace and security. But a realistic division of labour suggests that the UK should concentrate on security threats in Europe and its immediate neighbourhood, leaving its friends and allies in the Indo-Pacific to handle the problems in that region.

The answers to these questions are shaped to a remarkable degree by where the speaker stands on the causes, modalities, and consequences of Brexit and what that says about the UK’s long term relationship to Europe and its position in the world.

Both argue for a larger role, with the difference being that one sees Britain itself as capable of defining and executing that role either alone or with its global partners (USA, but also Australia, Canada and Japan, etc.), and the other sees Britain as only being able to play a significant role beyond its borders if it embeds itself in the EU.

But one problem remains. If Britain follows the ‘realistic’ course, concentrating on supporting security only in its European neighborhood, then who else from Europe is going to step in on Europe`s Asian security interests? A recent report from the Real Institute Elcano on Europe-Japan security partnership captures the current state of affairs. The UK-Japan quasi alliance comes through relatively strongly. Then would a rejection of Global Britain risk the end of meaningful European engagement in Asian security and the end of a global security role for Europeans?

Filed under Home

Part two of a good read on the current and potential presence of the UK armed forces in the Asia Pacific.

The Future of the British Armed Forces

What sort of involvement?

We do get suggestions what exactly the UK should deploy to the Asia-Pacific, but more often than not, they are just voices for grandstanding. Some are just list of ideals like this from the Henry Jackson Society (HJS) a whole list of what should be UK activities in the Asia-Pacific, now and post-Brexit. What really should be the UK’s plausible response to ensure stable security in the Asia-Pacific?

The UK military and political system actually is responding without such idealistic delusions of grandeur. First, the UK should continue or even try to slowly enlarge its permanent and temporary military presence in the region. British military deployments in Southeast Asia are already significant, despite what the analyst at HJS or other think tanks claim. The British Defence Singapore Support Unit (BDSSU), aka Naval Party 1022, is extremely well-valued by not just FPDA nations but other allied…

View original post 1,582 more words

Filed under Home

While many British people were either complaining about the weather or worrying about Brexit, Secretary of State for Defence Gavin Williamson and his delegation were abroad seven hours ahead of GMT plus 1 time. Namely, Williamson was in Malaysia, then Brunei and finally in Singapore for the annual Shangri-la Dialogue, or as known in social […]

via Gavin Williamson in the Asia-Pacific Part I — The Future of the British Armed Forces

Filed under Home

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg shakes hands with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at a joint press conference in Tokyo, 31 October 2017.

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg shakes hands with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at a joint press conference in Tokyo, 31 October 2017.

In 2011, Allies decided to invite all partner nations to establish Missions to NATO. Since then more than two dozen partners have done so, in order to further deepen ties with the Alliance.

Japan is NATO’s longest-standing partner outside Europe, with deepening cooperation since the early 1990s. Over the years, the Alliance and Japan have worked together to stabilize Afghanistan, to counter piracy off the coast of Somalia, and to strengthen partners like Georgia, Ukraine, Moldova, and Jordan. Today, Japan has liaison officers at NATO, including at Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe in Belgium, and Maritime Command in the United Kingdom. Japan also contributes a staff officer in support of the Alliance’s work on Women, Peace and Security.

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg visited Tokyo in October 2017, where he met with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, Foreign Minister Taro Kono and Defence Minister Itsunori Onodera. During the visit, both sides agreed to deepen cooperation in areas of common concern, including maritime security, cyber defence, nuclear non-proliferation, and gender mainstreaming in peace missions.

Filed under Home

Is the “Strategic Partnership” the new type of Alliance we have been waiting for? According to Rajesh Basrur & Sumitha Narayanan Kutty in The Hindu, it may not make sense any longer to strive for the exalted status ‘allies’, because “Alliances are passé“:

We live in a world today driven by “strategic partnerships”. States find themselves in an interdependent system where the traditional power politics of yesteryear doesn’t quite fit. After all, every major relationship characterised by strategic tension such as U.S.-China, Japan-China, India-China is simultaneously one of economic gain. The U.S. and China are each other’s chief trading partners, while China ranks at the top for Japan and India. Besides, India might confront China at Doklam but it also wants Chinese investment.

This is an observation with relevance for the Anglo-Japan relationship as well. According to Busrur and Kutty, strategic partnerships and alliances differ on the…

View original post 1,133 more words

Filed under Home